Why the Barents Sea continues to attract oil investment, despite lackluster results

One of the more active firms in Norway's emerging oil province thinks it may be sitting on a huge find.

On paper, the Barents Sea is a promising oil province for Norway as the country seeks to find new fields that can compensate for declining production from the North Sea. (Barring any major new discoveries, North Sea production can be expected to start declining in 2023.)

And the industry in Norway continues to see steady production for now. Output in 2024 will be close to the record set in 2004, according to the Norwegian Petroleum Directorate. This is due largely two huge finds: the Johan Sverdrup field, in the North Sea, which began producing in 2019, and the Johan Castberg field, in the Barents Sea, due to come on-line in 2023.

But perhaps somewhat worryingly for the industry, any growth after 2024 will need to come from projects that must be approved, discoveries that must be developed and resources that have yet to be discovered, Norwegian Petroleum Directorate said in its 2019 annual assessment.

For now, Norwegian Petroleum Directorate insists there is still oil to be had under North Sea, proclaiming on its website that the province is “still viable.” The discovery of the Johan Sverdrup field suggests this is true, but if Norway is to have a future as an oil producer, Norwegian Petroleum Directorate has repeatedly made it clear that the Barents Sea is where it must happen.

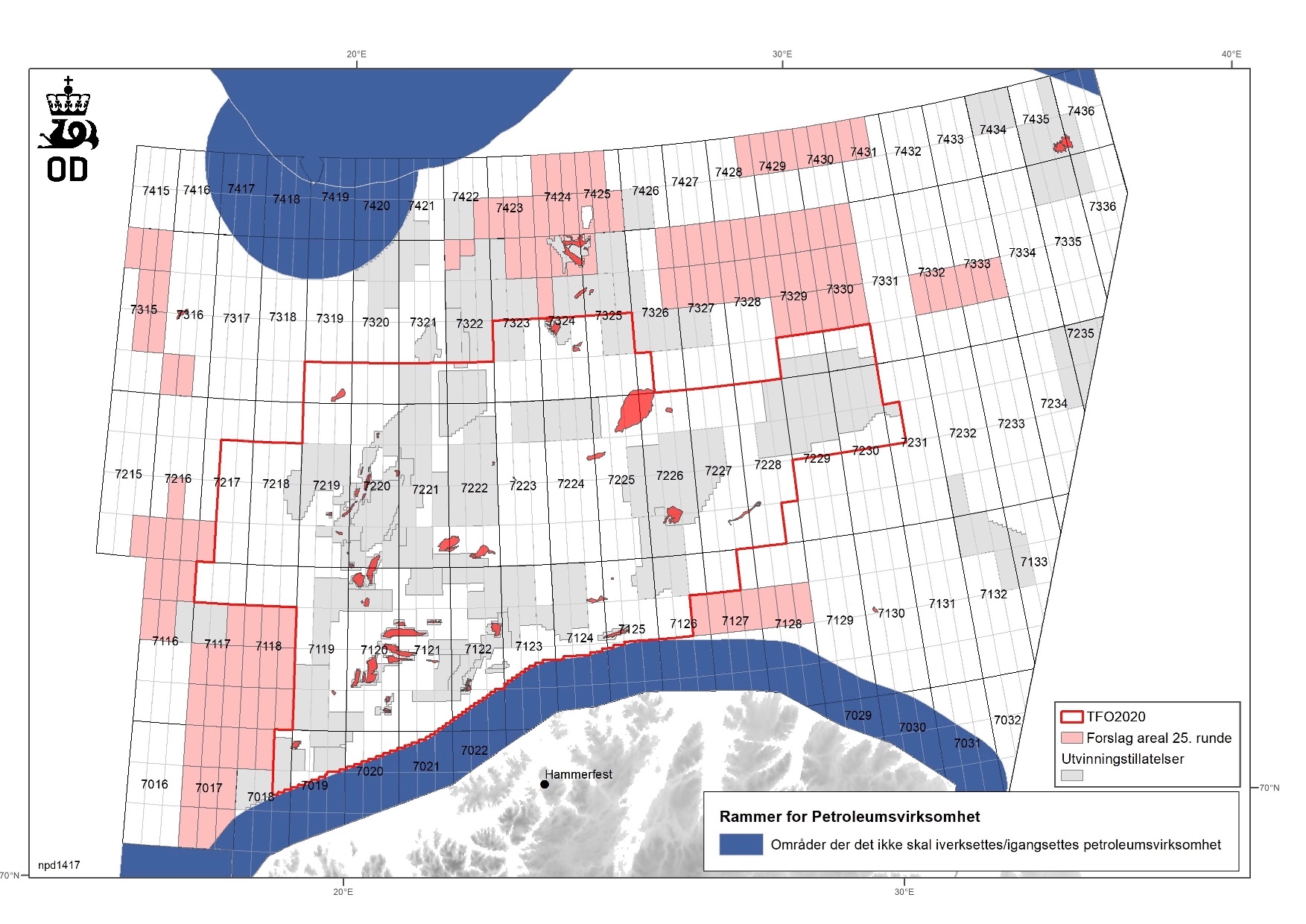

That it is still stumping for the North Sea suggests it may be concerned about the pace of development. If so, its response has been to open the Barents up even further to exploration. When it announced the sale of exploration blocks this past summer, 125 of the 136 blocks on auction were in the Barents (the areas shaded pink on the map above). This is a reflection of the fact that just two of Norway’s 88 active fields are in the Barents, even though an estimated two-thirds of its undiscovered offshore resources are there.

Seen optimistically, this means there is room for growth, and is perhaps why explorers are so enthusiastic about the Barents. While drilling in other parts of the Arctic has been wound down, due either to uncertain profit outlooks for the typically complex (read: expensive) projects, or to the environmental risks associated with drilling in remote areas, the classification of the Barents as an Arctic province has done little to scare off explorers.

“Arctic,” however, is more a description of the Barents’ location than conditions there: it is easily accessible, the warm water of the Gulf Stream makes it less prone to the challenging ice conditions that plague other Arctic operations and prospects are in closer proximity to land than other Arctic projects, meaning that building infrastructure to store, process and move products to market is feasible. Moreover, firms can use Norway’s reputation for environmental responsibility as a shield to deflect at least some criticism of their operations.

[The latest Norway oil find is another drop in Barents barrel]

In a sign of explorers’ faith in the future of the Barents, Lundin Energy, a Swedish firm, announced on Monday that it was purchasing existing licenses there, expanding its operations in a province it describes as one of its core exploration areas.

The $125 million deal was announced at the same time as the firm said it expects to begin drilling three exploration wells in the Barents before the year is out. Though some of Lundin’s recent wells have turned out to be dry, it reckons it may be sitting on gas and oil reserves amounting 800 million barrels of oil, larger than the Johan Castberg field by half.

Such facts would bode well for the future of Barents Sea oil, if it were not for its lackluster present. Discoveries have been more modest than hoped, and the existing operations have been plagued by all manner of mishap and, most recently, delays and cost overruns, leading to questions over how long companies would continue to explore there.

“We do have to have some material success at some point,” Nick Walker, a Lundin Energy executive who will take over as chief executive in January, told the Financial Times, a news outlet, in connection with this week’s purchase. “We can’t keep drilling forever.”