With Trump’s approval, Alaska-Alberta railway clears a key hurdle

The railway is intended to transport Alberta oil to Alaska ports, but could also be used to carry other goods or even passengers.

Last week President Trump announced that he will be issuing a presidential permit for the cross-border Alaska-to-Alberta, or A2A, railroad project. The project requires a special presidential approval to “construct, connect, operate, and maintain a railway” as it crosses the international border between the U.S. and Canada.

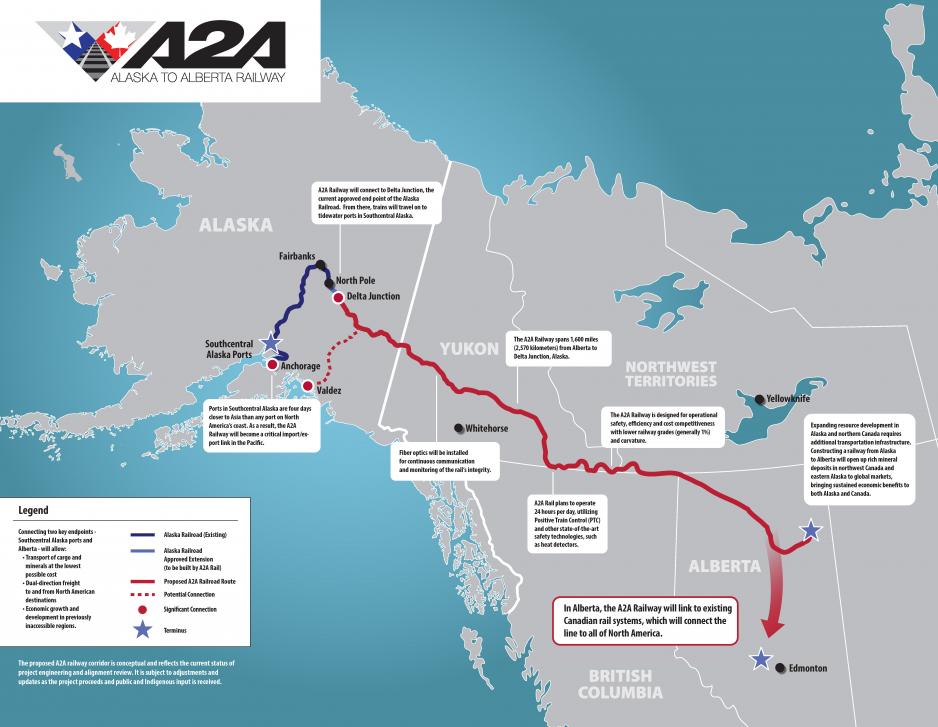

The A2A is a privately-financed railway project which was first studied nearly 20 years ago. The new 1,600-mile (2,570 kilometer) rail corridor would connect Alaska to Canada and onward to the Lower 48 states. The railroad would be instrumental in transporting oil from Canada’s tar sands in northern Alberta to the deep-water port in Anchorage. (Disclosure: ArcticToday board member Mead Treadwell also serves as A2A Alaska vice-chair.)

Currently, crude oil produced in Alberta has difficulty reaching sea ports for international export. Based on A2A documents the railway could transport 1-1.5 million barrels of bitumen per day based on eight loaded trains consisting of 192 rail cars.

The permit is an important step in moving the project forward. Next come environmental impact assessments, dialogue with Indigenous groups, and obtaining regulatory approval and eventually construction permits.

Biggest railroad project in a generation

The $17 billion project would construct a 500-foot-wide double-track rail corridor from Fort McMurray in northern Alberta passing through Canada’s Northwest Territories and Yukon before entering Alaska.

Alaska’s existing railroad, which currently terminates at North Pole east of Fairbanks would be upgraded and extended eastward to meet up with the planned terminus of the A2A in Delta Junction. Of the total cost, around $14 billion would be spent in Canada, with the remaining $3 billion reserved for Alaska.

“The issuance of a presidential permit is a significant milestone that will greatly assist with our continued efforts to build the A2A railway,” said Sean McCoshen, the founder of the Calgary-based company.

The A2A railways would provide the first rail link between Alaska and Canada and would be the largest railroad construction project in North America in several decades.

According to backers of the project, A2A would create more than 18,000 jobs in Canada and could contribute up to $45 billion to Canada’s GDP over 15 years. The current timeline estimates that construction would take four years with an opening of the railway in 2026.

A competing project, G7G (Generating for Seven Generations) also proposes the construction of a similar rail connection terminating in Delta Junction.

The bitumen, a very viscous form of petroleum, extracted in Alberta’s tar sands could either be transported to the port of Anchorage all the way by rail or could be transferred to the existing trans-Alaska pipeline which passes through North Pole and terminates at the port of Valdez.

The use of the trans-Alaska pipeline would however require upgrades to the pipeline and additional approvals.

Transporting Oil via Pipeline or Railroad

Transporting crude oil and bitumen via pipeline or rail both come with substantial risks. Transporting crude oil via rail has long been criticized by environmental organizations due to the significant risks in case of derailment. A number of minor and major accidents have occured in Canada and in the U.S. over the past decade.

While transporting viscous bitumen via rail may appear safer than more liquid crude oil, the bitumen is often made less viscous for transport with the use of flammable liquids increasing the risk of fires during a spill.

Canada’s National Railway Company, however, has developed a new technology to turn bitumen into solid pucks making it safer to transport.

“Once at its destination the pucks can be heated to return them into viscous consistency”, explains Heather Exner-Pirot, policy analyst for northern development and managing editor of the Arctic Yearbook, a peer-reviewed journal on Arctic issues.

Moving bitumen via pipeline also poses more risk compared to regular crude oil as the pipelines have to be heated to make the bitumen less sticky and have to run at higher pressures increasing the risk of leaks in pipeline. In short, transporting Alberta’s bituminous petroleum across North America to coastal areas remains challenging from an economic and environmental standpoint.

Overcoming environmental and economic concerns

“In contrast to other major infrastructure projects involving the transport of hydrocarbon resources, A2A has been able to bypass marine concerns of Coastal First Nations by choosing a route far from coastal areas not destined for Canada’s west coast in British Columbia,” says Exner-Pirot.

At the same time she cautions that the project is still in very early stages so a lot of Indigenous consultations are yet to come. However, “Northern First Nations are more practical and rail is more palatable,” Exner-Pirot confirms.

In general she says transport via pipelines makes more sense but in this particular case a rail corridor may be the way to go as it could also transport commodities, such grain or ore across the region.

It could even carry intermodal containerized goods which are currently shipped primarily via the sea to Anchorage. The new railroad could also potentially see passenger service.

The railway, however, will compete against Trans Mountain Pipeline, Line 3 and Keystone, all pipeline projects, raising questions of A2A economic feasibility. Future uses of bitumen, e.g. for the production of carbon fiber, which would have to be transported via rail could alter the economics in the railway’s favor, Exner-Pirot concludes.

While major regulatory obstacles remain the project is moving ahead and earlier this summer land surveys began in Alberta, to be followed by land clearing and construction of access roads before the end of the year.