Women’s issues are coming to the forefront of Arctic discussions

A coalition of Arctic observers are pushing for an Arctic Women’s Summit to help highlight issues of gender equality in the circumpolar region.

Women’s issues, from gender-based violence to political and economic parity, play a central role in the Arctic.

But until recently they’ve rarely come up in international discussions of Arctic issues.

That’s why Arctic researchers, activists, artists, policymakers and others are calling for an Arctic Women’s Summit, which would focus upon gender equality in the circumpolar region.

Tahnee Prior and Gosia Smieszek, both researchers focused on how institutions can be improved in the Arctic, are leading the charge.

In September, they organized an event at the University of the Arctic Congress in Helsinki for women in policymaking, business, justice, science, exploration, the arts and more.

The event brought together women from all across the Arctic, from Alaska to Russia, “which is key in all of this,” Prior said.

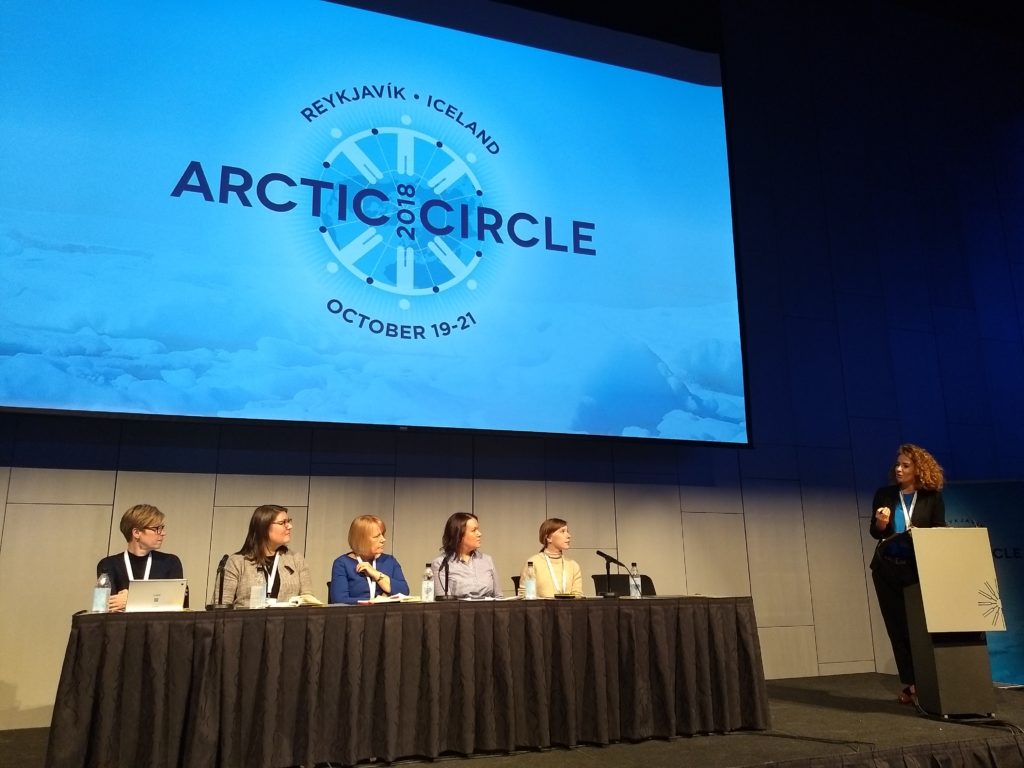

But their work didn’t end there. At the Arctic Circle Assembly earlier this month, they organized another event featuring politicians, policymakers, researchers and activists, who spoke frankly about the issues facing women in the Arctic.

Prior and Smieszek also created a website and a hashtag, #WomenoftheArctic, to build momentum toward a conference focused specifically on gender issues in the Arctic — and to highlight in general the many challenges women face across the north.

It all began a few years ago, when Prior attended an event in Canada focused on women.

“I thought, whoa, I hadn’t heard these perspectives before, and yet I’ve been to so many Arctic events,” she said. “There’s something wrong here; why is this happening?”

She began incorporating gender issues into her research. When she met Smieszek last year, the two discovered a mutual interest — and began planning to bring gender equality to the forefront of Arctic discussions.

“This is our first effort to do that, and our hope is that we can continue this conversation,” Prior said.

“We hope that the next step is an Arctic women’s summit.”

Katrín Björg Ríkarðsdóttir has worked on gender equality issues in Iceland for the past twenty years.

“We need to intertwine the discussion of gender into every topic,” she said at Arctic Circle.

“The Arctic is very diverse, and our communities differ a lot. But I still see that, regarding gender and women’s issues, we face common challenges.”

These challenges include traditional family structures that lead to imbalances in family responsibilities; gender-based violence; and the migration of young women to bigger communities and cities for jobs that are often not valued or paid the same as men, Ríkarðsdóttir said.

“I didn’t think much about gender equality before becoming a politician,” Sara Olsvig admitted. She’s been told she shouldn’t speak about topics like fisheries in meetings because she’s a woman.

Olsvig, the leader of Greenland’s opposition party, is now one of the country’s most prominent politicians. (Earlier this week, she announced that she would be stepping down from the leadership of her party.)

“During my time as a politician, I’ve been to very many Arctic conferences,” she said. “I’ve always asked myself why there was not more focus on social issues, on gender equality.”

In rural areas of Greenland, she pointed out, there is a gender imbalance in politics.

“We have a challenge in regard to rural areas, which I could imagine would be the same in other Arctic countries,” she said.

Overall in the country, she said, women make up 35 percent of Parliament and the municipal councils — although that ratio is lower in rural areas. And in settlement councils — the organizations working with very small and rural settlements — the ratio drops to one-quarter women.

There’s also a gap in income between men and women in Greenland — and the gap is even greater between foreign men and Greenlandic women.

Violence against women and children, especially sexual violence, continues to be a problem, she said.

“We need an Arctic Women’s Summit,” she said.

However, they cautioned, it’s also important to highlight gender inequality in other conversations, including existing conferences like Arctic Circle. Women’s issues, after all, are deeply intertwined with other Arctic challenges, and they should be present in discussions of those challenges.

“We don’t reach diversity if there are only men on a panel,” Olsvig said.

Jane Francis, director of the British Antarctic Survey, agreed. When you realize you need more women on a panel, she said, you seek voices that otherwise might not have been heard.

The panelists at the Arctic Circle event also agreed that conferences must include childcare. It would not only make working mothers’ lives easier, they argued; it would allow working fathers to take a more active role as well.

“We need to revive feminism in the form of gender equality and involve women and men,” Olsvig said.

While Prior and Smieszek take the next steps to make an Arctic Women’s Summit a reality, they continue to shine a light on women’s issues online and on social media.

“Because gender is not plan B,” Prior said.