World Wildlife Fund: Canada’s unprepared for fuel oil spills from Arctic shipping

Though fuel oil spills represent the worst environmental threat posed by increased Arctic shipping, authorities, including the Canadian Coast Guard, are ill-prepared to cope with them, the World Wildlife Fund’s Canadian wing says in three related reports issued earlier this month.

“An Arctic shipping oil spill would devastate the surrounding marine environment, including the destruction of habitat for polar bears, seals, walrus, sea birds, as well as beluga, narwhal and bowhead whales,” WWF Canada said.

But at the same time, Arctic communities, and not the polluter, would bear the most of the consequences, the WWF said.

“Not every community has response equipment for a marine spill. In the communities that do, the equipment is limited and could be used to respond to only a very small spill.”

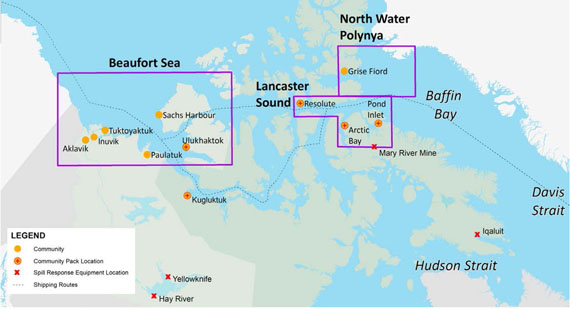

Of the WWF’s three reports, one provides background information on Nunavut’s High Arctic, the other provides background on the Beaufort Sea region and one summarizes conclusions and recommendations made from studies on the two regions.

For Nunavut, the WWF’s researcher looked at oil spill response capabilities in four of Nunavut’s most northerly communities, all of which lie around Lancaster Sound: Grise Fiord, Resolute, Arctic Bay and Pond Inlet.

Of those, Grise Fiord and Arctic Bay see the smallest number of ships, while Pond Inlet, especially with the additional ships that now serve the Mary River iron mine, sees the most marine traffic.

During the 2013 open water season, that region saw 27 adventure and tourism voyages, 12 of which involved passenger vessels as opposed to yachts.

And in 2013 eight tankers and 14 cargo vessels passed through Lancaster Sound. That included the Nordic Orion, which transported a shipment of coal from western Canada to Finland, and is the first bulk carrier to transit the Northwest Passage.

As for Mary River, 13 voyages carried ore out of Milne Inlet through Eclipse Sound past Pond Inlet in 2015, and more vessels carried fuel for the Mary River mine.

At the same time, many of those ships still use heavy fuel oils, or HFOs, which would pose the greatest risk in the event of a spill.

“Heavy fuel oil (HFO) is the fuel most often used by large shipping vessels. Of all the marine fuel options, it is also the most damaging in the event of a spill,” the WWF Nunavut report said.

Some other vessels use intermediate fuel oils, or IFOs, a blend of marine gas oil and heavy fuel oil.

And others use Arctic diesel fuel, which the WWF says is a more refined product than HFOs and IFOs.

Arctic diesel fuel, which is designed to work at low temperatures. dissolves and evaporates more quickly than heavier fuels but at the same time, it’s more poisonous for people, animals and plants when it’s first released.

Overall, the communities around Lancaster Sound are not prepared to cope with a major spill from a commercial vessel and neither is the Canadian Coast Guard, the WWF found.

“As this report notes, Grise Fiord has no CCG-stockpiled oil spill response equipment and the other three communities have equipment that could clean up only a very small amount of oil.”

The Coast Guard’s community packs included enough equipment to clean up only about one tonne of spill oil: 1,350 to 3,650 feet of boom, a skimmer, a 16-foot aluminum boat, a storage tank, plus shoreline kits comprising rakes, shovels, pitch forks and tarps.

Also, the Government of Nunavut’s Petroleum Products Division provides each community in Nunavut with 150 feet of floating boom, 200 feet of rope, two bales of absorbent pads, four empty 205-litre drums and other equipment.

But there is no guarantee that any of this stockpiled spill response equipment would even work, the WWF said.

That’s because it’s not checked regularly and it’s in uncertain working condition.

And the Coast Guard response packs may not even be accessible to residents of some communities.

“Some communities don’t have a key for the locked storage containers because the CCG is concerned about maintaining responsibility for the equipment inside,” the WWF said.

As for the Coast Guard, it’s unlikely that any of its vessels could reach a spill fast enough to make much of a difference.

That’s because there are usually only three Coast Guard ships responsible for the entire Northwest Passage.

“Moreover, there is no CCG process in place to ensure that sufficient equipment will ever exist in any of the villages to clean up the amount of oil that could spill from ships currently travelling in the region,” the WWF report said.

Other problems include:

• low numbers of trained oil spill responders;

• poor communications infrastructure, especially cell phone and internet networks;

• no hazardous waste disposal facilities in the Arctic; and,

• the Arctic climate, such as high waves and strong winds that can make it impossible to contain oil spills using floating booms.