‘Zombie fires’ helped make this worst wildfire season ever recorded in the Arctic

Some of last year’s fires never actually went out, driving a season that saw far more acres burned and emissions released than previous years.

Wildfire causes can usually be neatly divided into those sparked by natural causes and those set by humans — intentionally or unintentionally.

But this year, scientists studying wildfires in the Arctic are popularizing a third, supernatural-sounding, cause: zombie fires. These are, in fact, fires from a previous year that smoldered underground but never went out.

The term came about after scientists the Copernicus Atmosphere Monitoring Service, an EU agency, registered big fires in Siberia in May, two months earlier than normal. They were mostly in areas that burned last summer, which led them to suggest that this year’s fires were actually last year’s fires that had survived the winter by burning peat and other underground material. Once conditions are dry enough, the fires take hold aboveground and pick up where they left off.

When theorized in May, CAMS reckoned that this would lead to a “cumulative” effect that would feed into the 2020 fire season, causing a second consecutive year of large-scale, long-term fires in the region.

[Arctic wildfires are on the rise — but we still know very little about their health effects]

As is turns out, this year was not just bad but worse than anyone has ever seen: Records have only been kept since 2003, but this year’s fires well exceed the damage and carbon-dioxide emissions caused by last year’s record-setting fires.

Between January and August, Arctic fires released 244 million tons of carbon dioxide into the atmosphere, according to CAMS. The full-year figure for 2019 was 182 million tons. Prior to that, the highest amount was 110 million tons, in 2004.

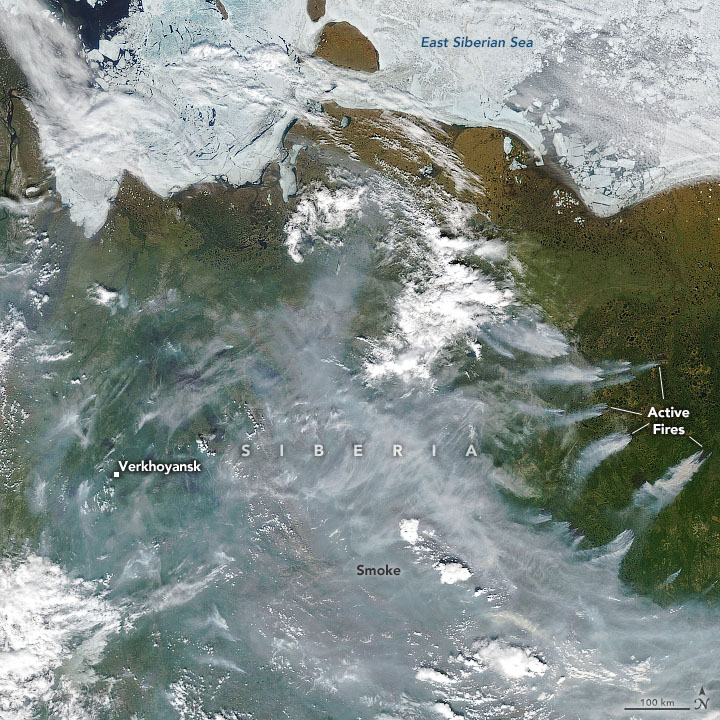

Much of this year’s emissions came from fires burning in Russia. The fires there, which coincided with a heatwave in Siberia that saw temperatures approach 40 degrees Celsius (104 degrees Fahrenheit), are estimated to have released 200 million tons of carbon dioxide, more than the annual emissions of many mid-sized countries.

According to Russia’s wildfire monitoring agency, there were more than 18,000 separate fires in the Far East; a total of nearly 14 million hectares burned. Other parts of the region saw fewer fires than normal, but regions that were downwind of the Siberian blazes still suffered from them. (In addition to being a public health issue, scientists suggest the smoke from Arctic fires could exacerbate global warming if the soot from the smoke settles on ice.)

Those figures have caught the attention of the international scientific community, with top journals Science and Nature both writing about the danger these fires portend.

Local and regional groups are also on the case.

The Gwich’in Council International, for example, is leading two Arctic Council projects related to the issue. One of them, being carried out under the auspices of the council’s Emergency Prevention, Preparedness and Response working group, is looking for ways for Arctic countries to pool resources and coordinate training, adding wildfires to a list of cross-border threats that includes oil spills and accidents at sea.

Where there is fire, there may very well be a reason for closer cooperation.